Over 50 participants from all over the world gathered at IMD in September 2015 to hear how the Sharing Economy is ushering in new business paradigms in traditional industries such as rental accommodation and banking. Professors Albrecht Enders and Andreas König highlighted the difficulty for incumbent players to understand – and then react to – the disruptive innovations which sharing- based businesses bring to markets, and how in the future these innovative models for capturing value can be integrated into incumbents’ modus operandi.

Is the Sharing Economy here to stay? For many incumbents whose industries are being disrupted by sharing-based business models, the initial reaction has been one of denial. Attitudes range from dismissiveness – “These upstarts can’t possibly compete with us” – to scorn: “They aren’t trained industry professionals. They’re amateurs.” Another common form of denial is to predict that the sharing economy is doomed because of the fact that it often operates outside of regulatory frameworks (or in legal grey areas). According to this scenario, governments will eventually crack down on the Ubers of the world and then Uber will be forced to pull back from its expansion into the private turf of taxi drivers’ unions.

But by now, more and more established players are realizing that the Sharing Economy is indeed here to stay. Sharing businesses such as Fiverr, Skillshare, TaskRabbit, HelpAround, Lending Club, TransferWise, nimber and sharemystorage.com epitomize this new trend. Their attraction lies largely in the so-called frictionless nature of their digital platforms, which allow easier and more transparent peer sharing as well as product and service transactions. Users are flocking to these online marketplaces in ever greater numbers. In fact, the revenues of “shared” businesses such as car sharing, online staffing and peer-to-peer lending will likely catch up with the revenues of their traditional rental-sector counterparts within ten years.1

As the Sharing Economy blossoms and grows, established players tend to move to the next reaction stage: puzzlement. Because the sharing-based business models are so different from their own, incumbents struggle to understand them. How do these sharing models function? What value do they bring to their users? For example, one can imagine the staff of a food-sector giant like Nestlé discovering the app called LeftoverSwap. In this application, people post pictures of their leftover food for others to select and then pick up. The app features a photo gallery of unfinished meals to choose from, ranging from pizza to Chow Mein. And though this type of food sharing may seem anecdotal, it lies so far outside of the norms and the corporate culture of food and beverage companies – which are based on strict hygiene and food-sourcing rules – that it can only be perceived by industry professionals as alien. For incumbents, the question becomes: how do we compete with something that we don’t fundamentally understand?

Zencap: Disrupting the banking system

Zencap is a German startup that specializes in providing loans to small and medium businesses. Its goal is to replace banks in lending to SMEs. At its inception, Zencap gave itself the ambitious goto-market strategy of going live with its product within 60 days. Zencap met its target, and went on to become the fastest growing online lending marketplace in continental Europe. Co-founder and managing director Christian Grobe laid out the firm’s three cornerstones: first, 24/7 service and everything online; second, focus only on the €5,000 to €250,000 segment; and third, ease of use and a 10-minute application process. Zencap was acquired by Funding Circle in October 2015.

Of course, leftover swaps will never put food-industry giants out of business. But some sharing businesses are taking off. Airbnb is a case in point. Airbnb, which helps people rent out their houses, apartments and spare rooms for short stays, has grown exponentially in a few short years. Its number of listings and annual guests has roughly tripled from 2013 to 2014. The company is expected to top $900 million in revenue this year, and projections for the year 2020 augur a tenfold increase to $10 billion in annual revenue.

At this stage, Airbnb has become impossible for the hotel industry to ignore, especially with its latest round of fundraising, which vaulted the company’s valuation up to $25.5 billion. This places Airbnb beyond the market cap of major hotel chains such as Marriott and Starwood. Yet many hotel industry executives still struggle to grasp the value that Airbnb provides to its customers. As one such executive commented: “I find it hard to imagine the kind of people who use these services. I consider it a terrible thought, having to stay in someone else’s home. And the mere idea of being away for a couple of weeks and having somebody else stay in my apartment sounds like a horror vision to me.” Other executives seek to puzzle out the fundamental differences between the two models: “Airbnb is an inventory solution, not a curation model like a hotel” and “They wash their hands of all the issues associated with the actual fulfilment side of the business, other than processing the reservation.”

This lack of understanding is not surprising, given how different Airbnb’s business model is to traditional hotels’. In a nutshell, Airbnb is asset-light, it owns no real estate and its consumers are often its suppliers. Its quality control system is also distinct. Instead of the classic five-star rating scheme dear to hoteliers, Airbnb operates on a system of peer reviews. These reviews create an alternative trust mechanism that emboldens users to entrust their homes to complete strangers.

Several of these Airbnb characteristics, such as the “consumers as suppliers” model, exemplify the changes brought by peer-sharing businesses. And these changes introduced by the Sharing Economy are not incremental – they represent discontinuous innovation, as summed up in Figure 1.

Figure 1: How shared businesses are a discontinuous innovation: A comparison of traditional and shared business models

For traditional players, understanding sharing-based businesses requires nothing less than a paradigm shift. But what exactly is a paradigm? It is the sum of processes, operative elements and basic assumptions that make up a business. As an illustration, the “hospital paradigm” features patients, doctors and nurses functioning in fixed roles. It also includes physical spaces: beds, wards, waiting rooms, operating theatres and a reception desk.

The Sharing Economy turns many traditional paradigms on their heads. So for example, a big challenge for an incumbent may be: what do you do when your competitors don’t even want to make money? This is the question that traditional encyclopedia manufacturers faced when Wikipedia emerged. Prestigious companies such as Brockhaus in Germany, which employed dozens of Ph.Ds. to generate content, could not fathom how unpaid amateurs could ever crowdsource a credible product.

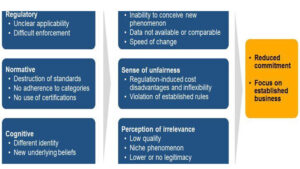

In some industries, there is also the issue of compliance. As one hotel executive pointed out, “Entrepreneurial companies just start doing something on the fringes and get away with it; it’s not easy to regulate them by law.” The perception that start-ups are not subject to the same ‘rules of the game’ is a raw point for established companies.

On a more general level, traditional businesses have achieved excellence because they master their business paradigms: they possess the industry knowledge, the talent, the networks, the assets and the value chain that allow them to compete successfully. But in times of discontinuous change, this mastery can actually prove limiting. It can dampen the search for new ideas and reduce openness to change. It can also blind companies to the existence of untapped opportunities. On this point, one participant commented: “It’s hard to see the ‘little holes’ in the regulation fortress if you’re trying to drive through it with a tank!”

In short, it’s because of the way shared businesses challenge paradigms that incumbents tend to perceive them as confusing, unfair and irrelevant, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Basic model of responses to shared businesses

A new way of thinking about value

We have seen that for incumbents, paradigm-breaking innovation is both difficult to understand and tough to respond to. However – whether it is in the Sharing Economy or in other cases of discontinuous change – a useful way for established players to grapple with these sudden innovations is to adopt more structured ways of thinking about strategic change. The key is to examine how your company creates value which is unique and sustainable, as compared to competitors. This allows you to capture the extra value and translate it into profits.

A well-known example of value capture is Apple. What allows the Cupertino giant to obtain its market capitalization of over $600 billion? The first step is to examine how its customers perceive the benefits of Apple products. These benefits include the unique ecosystem of devices, the iTunes platform, the overall brand and the ease-of-use of the operating system. Less intuitively, benefits also include the aspects that make the products “sticky” – in this case, the high switching costs incurred by consumers who wish to leave the Apple ecosystem. The second step is to add up the firm’s total costs (labor, components, marketing and so on). If we subtract the costs from the perceived benefits, this allows us to measure the value created.

The next phase is to analyze how this value can be captured by the company. The important thing to understand here is that not all value is created equal. Value that is both unique and sustainable over time is much better than value that your competitors can imitate. It is thanks to these characteristics of uniqueness and longevity that a firm can charge higher prices. In contrast, a company that produces attractive but easily available products (or has an offering that degrades over time) is hampered by a competitive discount and must therefore cut its prices. The end result is that some companies can capture more value than others and then monetize it.

Overcoming incumbent inertia

The upheavals caused by the new Sharing Economy should not be considered only as a threat by established companies. The clash between old and new paradigms is also an opportunity for incumbents to examine more closely and more creatively the value that they currently generate. The fact is, traditional business paradigms tend to contain elements that are taken for granted. Privacy and impersonal transactions are two examples of benefits that classic hotels provide. However when we book a hotel stay, we rarely think about these advantages – instead, we tend to think of the quality of the hotel experience as a sum of its amenities, décor and prestige of location. But users of Airbnb are now realizing that privacy is not a given – it is a precious benefit. This is because Airbnb requires that its users submit a personal application to the renter, who can either accept or refuse them. After the stay, both the user and the renter must rate each other on the web platform and may also provide comments. Giving bad reviews of a stay in someone’s home can be both socially awkward and bad for one’s reputation within the online rating system. Hotels, in contrast, allow clients to preserve their privacy.

A better understanding of what unspoken paradigms undergird their businesses can help companies make sound strategic choices. These choices include making tough trade-offs between what “perceived benefits” they want to invest in, on one hand, and what costs they want to reduce, on the other. The critical endeavor for top teams is to develop an overarching perspective. This involves listening to the customer insight department, weighing costs and continually scanning the competitive landscape. Top teams must find a way to look beyond these competing goals to gain a balanced view. And above all, companies must learn to overcome incumbent inertia and engage with the innovative models that the Sharing Economy has introduced to the world.

1- PwC Analysis: “Sharing economy sector and traditional rental sector projected revenue growth.”

Discovery Events are exclusively available to members of IMD’s Corporate Learning Network. To find out more, go to www.imd.org/cln