- Angaza was founded in 2010 with the aim of eliminating energy poverty for populations living at the base of the pyramid with no access to electricity.

- As a for-profit social enterprise, it needs to be financially sustainable while fulfilling its social purpose.

- From its initial business model of selling portable solar lights to end customers, Angaza pivoted to providing pay-as-you-go monitoring and metering software to solar product manufacturers.

- In addition to philanthropic impact investment, Angaza has attracted traditional venture capital investment.

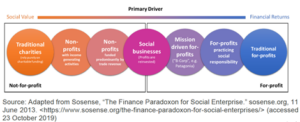

Creating social impact and making financial returns do not have to be mutually exclusive. A social business is one in which both goals coexist comfortably. In fact, a social business is created with the express purpose of fulfilling a social mission but with the proviso that it also needs to be financially sustainable. With its goal of combining commercial and social missions, a social business is often also called a hybrid organization (see Figure 1 for different organization types on the social value vs. financial returns spectrum).

The broader issue

Angaza is a for-profit social business that began as a solar light maker and then pivoted to become a provider of pay-as-you-go (PAYG) software solutions. Angaza’s experience highlights many of the challenges an early growth stage social business faces, including obtaining funding, refining its business model and value proposition, and scaling. In addition, Angaza faces issues specific to the base of the pyramid, including the low income of its end customers and traditional investors’ lack of familiarity with these markets.

Figure 1: Business model spectrum: Not-for-profit to for-profit

Fighting energy poverty

Angaza was founded in 2010 by Lesley Silverthorn Marincola, then a recent Stanford graduate. One of her courses – Designing for Extreme Poverty – inspired her to set up the company. Although Lesley had always been interested in addressing poverty in emerging markets, the class showed her the potential entrepreneurial opportunities. Through a student project that took her to Africa, she recognized how solar-powered lights could be used to replace kerosene lamps, which were toxic and easily combustible, thus improving the standard of living of people at the base of the pyramid (BoP)[1] who had no access to electricity.

Angaza’s first product was a portable solar light created following human-centered design principles. However, Lesley was unable to obtain buy-in from Silicon Valley investors she approached:

You are talking to investors who are investing in the next iPhone app, and I’d walk in to these investor pitches and say, “Hey, we’re developing hardware – for Africa.” Investors in the Valley didn’t quite get that.

The prevalent Silicon Valley view was “hardware is hard, hardware is expensive, hardware takes a long time.” In addition, Lesley’s product was competing in a crowded market. There were already many solar light manufacturers with established distribution networks, such as d.light design and Barefoot Power. Furthermore, although Angaza’s solar lights retailed for $50 to $60 – well below the $150 that the lowest tier of global BoP households (with an income of $500 per annum) spent annually on energy consumables[1] – customers did not have enough money at their disposal at one time to make the purchase up front.

A new approach

Hardware to software

After working for over two years on her solar light but failing to gain traction, Lesley was about to call it quits. Her brother, Bryan, who had a background in machine learning and artificial intelligence, got her thinking in a new direction, however. Rather than selling hardware, he proposed software-based solutions that could solve one of the biggest pain points Angaza was facing – making the hardware affordable enough for the target market.

To address the issue of affordability, Angaza turned to pay-as-you-go (PAYG), a system where customers can pay for units of time for using solar lamps rather than paying upfront for the entire solar lighting system. Bryan, who had joined Angaza as chief technology officer (CTO), experimented with ways to make Angaza’s solar lights purchasable over time. He faced two technological issues: Finding a way to collect money without visiting customers – often in remote locations – and devising a method to turn the device on and off depending on payment.

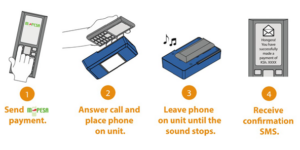

In 2012, a small solar lantern with PAYG functionality was launched. Customers could purchase the mobile solar light for a small initial fee and preload it with credit. When the credit ran out, the customer used mobile money – popular in East Africa – to pay Angaza for more credit with their mobile phone. When the payment was confirmed, the phone would play a high-frequency sound clip. The payer then held the phone to the solar light so that the sound could be picked up by a microphone in the light. The sound acted as a key to unlock the corresponding amount of energy credit (see Figure 2). Usage data would also be transmitted back by the phone. The customer paid for the outstanding balance on the phone unit over time and ultimately owned it outright.

Figure 2: Angaza’s PAYG-embedded solar product

Philanthropic impact investing

On the financing side, Angaza approached philanthropic impact investors rather than pitching only to traditional venture capitalists (VCs). A traditional VC seeks a high-return exit from the start-ups in which it invests; this usually involves companies that can scale rapidly. Philanthropic impact investors, by contrast, aim to create impact by supporting sustainable social enterprises to build viable organizations and unlock sustainable social innovations. They also have a longer investment horizon and lower threshold for financial returns, and are therefore willing to invest in early-stage social businesses with riskier profiles. Often, philanthropic impact investors are more willing to support enterprise building and initial experimentation with the business model. They work closely with impact entrepreneurs, offering significant time and mentoring. In fact, the amount of in-kind support philanthropic impact investors contribute to enterprise building can be equal in value to what they provide in loan or equity financing. Since they expect a cash return on their monetary backing, their contribution is considered an “investment,” not “charity.”

In January 2012, Angaza contacted the elea Foundation for Ethics in Globalization, an active philanthropic impact investor based in Zurich, Switzerland. elea thought the PAYG technology was promising and sent the solar light with PAYG functionality for a technological evaluation. Given the encouraging product test results, elea decided to invest $350,000 in the start-up in Fall 2013, making it the largest investor in Angaza’s $1.5 million seed round.

From B2C to B2B

Although Angaza knew that the PAYG technology was feasible, it also realized that manufacturing hardware in general was difficult and expensive as scale efficiencies were needed to lower costs. At the same time, other solar light manufacturers had seen the potential of Angaza’s PAYG technology and approached the start-up to discuss embedding its technology in their products. Angaza’s leadership team felt that transitioning into a software technology provider was the way it could make an impact at scale and bring affordable energy to many. In 2014, Lesley and her team decided to pivot away from hardware and instead provide PAYG-embedded metering and monitoring technology to third parties. By 2015, Angaza had stopped selling its own solar lights and fully migrated from a business-to-consumer (B2C) to a business-to-business (B2B) model, building cross-sector partnerships with manufacturers, distributors and mobile network operators.

Did it work?

Collaborating with its manufacturing partners, Angaza expanded beyond its initial market of East Africa to the rest of Africa and other parts of the world. It also worked closely with the manufacturers to integrate its PAYG technology into a broader portfolio of products, including cookstoves, solar water pumps and televisions. With this growing product portfolio, Angaza also introduced new PAYG technologies, including keycode and GSM, which involved embedding a SIM card.

Since Angaza’s seed round in 2013, in which it raised $1.5 million, the company had successfully raised $4 million in additional seed funding in 2015, followed by a further $10.5 million in its Series A round in 2017. The funding came from a variety of sources, including patient capital from philanthropic investors and impact investors – such as the Social Entrepreneurs’ Fund, Rethink Impact and Emerson Collective – and more traditional equity capital from outfits such as Salesforce Ventures. By early 2018, Angaza was on track to enable the sale of almost one million solar products. It was also chosen from hundreds of candidates worldwide as a recipient of the 2018 Skoll Award for Entrepreneurship, which recognizes leaders and organizations that “disrupt the status quo, drive sustainable large-scale change, and are poised to create even greater impact on the world.” Winners were awarded $1.25 million and given access to a global network of innovative leaders.

Some impact investors were concerned about Angaza veering away from its original impact focus, especially for a prospective exit, but Lesley never accepted from investors mission drift clauses:

We did not want to put a mission drift clause in our bylaws. That comes from the belief that we, as the founding team, trust ourselves and our existing investors to make the right decision about the exit. It’s not just going to be about what completely maximizes profit if it somehow has a negative impact and goes against our mission in some way.

Fortunately, Lesley had yet to feel that she had to compromise impact for financial returns:

I think we’ve done a really good job of designing a product that fits this market. We’ve designed our business model such that every dollar of revenue we make has an impact; we have never had to make a choice that would compromise one or the other.

Takeaways

- Pivoting and changing a company’s value proposition does not inherently mean deviating from the company’s purpose when impact is at the core of the business. Instead, it can bring further opportunities, on both the impact and the financial sides.

- Pivoting is expected in the early growth stage while impact entrepreneurs are developing the right business model to scale.

- There is a broad spectrum of investors with differing requirements for social impact and financial return. Social businesses can approach the type that best supports their needs at a particular stage.

- It is possible to have impact and make a profit at the same time. As Angaza’s founder, Lesley Marincola, a, puts it: “Impact is our core business as we make money.”

THIS ARTICLE IS BASED ON THE IMD CASE IMD-7-2335, AVAILABLE FROM THE CASE CENTRE AT THIS LINK.

References:

[1] Hammond, A. et al. “The Next 4 Billion.” World Resources Institute, March 2007 <https://www.wri.org/publication/next-4-billion> (accessed 12 February 2020).