A turtle struggles to escape from a six-pack ring tangled around its neck; other sea life nibble away at plastic bags, thinking they are jellyfish.

While images like these lay bare the impact of plastic pollution on wildlife, there’s also a much less visible threat: microplastics. Measuring less than 5mm, these tiny plastic pieces result from the breakdown of larger plastics. And they’re everywhere – from fruit and vegetables to bottled water. Some studies have even found them in prenatal human placentas.

“We all have it all in our bodies,” says René Rozendal, co-founder and managing director of Paques Biomaterials. “There’s still a lot unknown about the long-term effects this will have; it’s basically a massive experiment we’re doing with mankind.”

The world currently produces 430 million metric tons of new plastics every year, according to the UNDP. And this rate is expected to triple by 2060. “This is unsustainable in the long term,” says Rozendal.

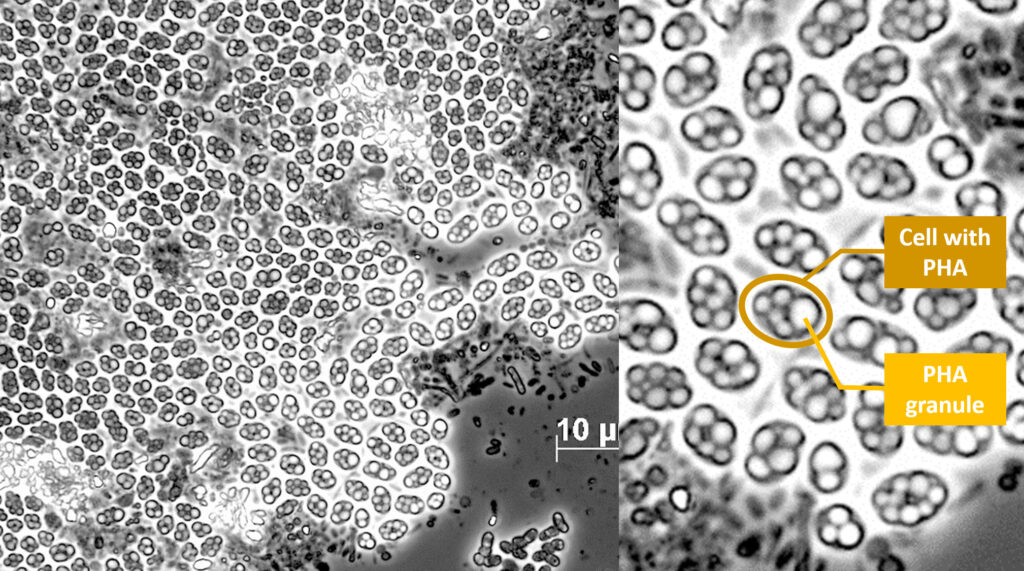

Based in the Netherlands, Paques Biomaterials is developing a natural alternative to plastic from organic waste streams. It is working to scale a technology that encourages microbes to overeat organic pollutants found in industrial wastewater or solid organic waste, such as food waste and wastewater treatment sludge, and produce “fat” in their cells. This bacterial equivalent to fat is a biopolymer called PHA, which can be used as a natural alternative to plastic.

“We’re basically creating obese bacteria,” explains Rozendal, noting that some bacteria can store up to 80-90% of their cell weight in the form of this compound. Paques Biomaterials then extracts the PHA as a powder, known as Caleyda®, which can be melted into any shape or form to make plastic-like products. Moreover, bacteria also consume PHA as food, so if these materials end up leaking into nature, they will decompose without forming harmful microplastics. This means Caleyda® has the advantages of conventional plastics without its disadvantages.

When preparation meets opportunity

Rozendal studied biochemical engineering at Delft University of Technology, where he met Joost Paques, whose family was the majority shareholder in Paques BV, a company that built large-scale industrial water treatment plants. Rozendal began working for the company part-time while he completed his PhD and eventually joined full-time in 2011 after a stint in Australia. He worked his way up to Chief Technology Officer and one of the R&D projects involved this natural alternative to plastic.

Rozendal admits he had never considered an EMBA. But when his CEO offered him the opportunity, he chose IMD for its relatively small class sizes and strong links to industry. Since Paques’ business model was project-driven, Rozendal devoted much of his EMBA coursework to figuring out how to embed this new technology business into the broader organization. Once he graduated, however, events happened that changed his plans.

Joost Paques approached Rozendal to tell him the family was selling the company, creating the opportunity to carve out the technology into a separate business. Paques brought the starting capital, and soon after, Rozendal, who became co-founder, shareholder, and managing director, put his EMBA assignments on strategy, customers, and cultural transformation into practice.

“All the previous coursework on how to set this up, what kind of market to focus on, the strategy, how to bring this forward – all these things came together, and I could actually execute them within this carve-out,” he says.

His EMBA also strengthened his leadership skills, preparing him to go from a specialist job to a role that encompasses everything from hiring and fundraising to cleaning the staff kitchen as they build the company from the bottom up.

From start-up to scale-up

Despite it being a tough market to raise funds, Paques Biomaterials secured €14m ($15.3m) in January 2024 to build a pilot extraction facility for its PHA. The final investment decision for full-scale production is expected in 2025, with sales scheduled for 2027.

Growing consumer awareness about the scourge of microplastics plus a slate of new regulations designed to reduce the amount of plastic waste are acting as tailwinds, says Rozendal.

The EU has already introduced regulations restricting the use of plastics in controlled-release fertilizers. From 2026, only fertilizers with biodegradable plastic coatings will be allowed on the market in a bid to stop the microplastics from making their way into the soil, accumulating in plants, and ending up on our plates.

Moreover, the UN is in the process of drafting a treaty based on legally binding global rules and circular economy measures, which is expected to be finalized by the end of 2024. Regarded as the plastics equivalent of the Kyoto and Paris agreements for climate, the treaty is seen as an opportunity to accelerate systems change and end plastic pollution.

All this presents an opportunity for Paques Biomaterials, which up until now has only been developing small quantities of Caleyda®. According to European Bioplastics, the global bioplastics market is expected to grow to a million tons by 2028, up from 100,000 tons in 2023. The new funding will enable them to generate larger quantities so they can work on business development with potential customers – ranging from paper companies, makers of adhesives, and those who use plastic for chocolate bar wrappers.

Depending on the success of the extraction plant, Paques Biomaterials plans to build a full-scale extraction plant, which will require further funding. Yet as a “tech for good” company with a long development horizon, it also faces challenges. Most venture capital firms are looking to invest in startups that will enable them to see a return on investment within seven years, meaning the company must scout for investments from government organizations or family funds with a longer-term perspective.

Another challenge is that bioplastics are expected to remain up to three times more expensive than plastics made by fossil fuels for the foreseeable future.

“In the end, we are not paying the fair price,” said Rozendal. “Nobody is paying for the carbon dioxide emissions associated with fossil fuel-based plastics; nobody’s paying for the associated microplastic pollution. If we were to incorporate this into the price, it would be a no-brainer.”